|

Margate Crime and Margate Punishment

Anthony Lee

10. Margate Criminals.

There are few ways for us to learn about the lives of the poor – they seldom leave much trace in the written record, unless, that is, they end up in court. Those in authority spent much of their time ensuring that the poor behaved properly and did nothing to frighten the quality; the poor were often taken to court for very minor offences. While Margate remained within the jurisdiction of Dover, their trials would take place at Dover before the Mayor and a group of the Dover jurats acting as magistrates, at the Court of General Sessions and Gaol Delivery, a court equivalent to a County Assizes.1 The court had jurisdiction over offences up to and including capital felonies, although by 1835 ‘within the liberties of the Cinque Ports . . . capital offences, which are likely to be followed by executions, are generally sent for trial at the assizes of the adjoining county’.2

Those found guilty by the court could be punished in a number of ways. In the case of a convicted felon, that is, someone convicted of a felony, the judge had little choice; the sentence was execution, although after 1718 this was often commuted to transportation, usually for seven or fourteen years. The more well-to-do amongst the lesser offenders might be punished with a fine, the less well-to-do with a whipping. For more serious crimes there were the pillory and the stocks. By the 1820s many of these punishments were being replaced by short periods in gaol, usually with hard labour.

Executions were rare at Dover. When William Turmain, a Margate shoemaker, was executed at Dover on Monday March 8th 1813, it was said to be the first at Dover for about 28 years.3 The case was an early triumph for the new Cinque Port Magistrates: the arrest of Turmain and his accomplice, Edward Herod, was said to be due to the ‘activity of two of our new Magistrates (the Rev Mr Baylay and Edward Boys esq) and by the cautious proceedings of their clerk and peace officers acting under him’.4 William Turmain’s father was a silk weaver in Canterbury, and Turmain, ‘after receiving a common education,’ was trained as a shoemaker, moving to Margate to set up his own business.5In Margate he took on a young apprentice, Richard Twyman, but ‘instead of receiving good moral instructions we find Turmain initiating him in the very worst principles of vice by prevailing on the boy to steal a tub of butter’.5 Turmain was suspected of the theft and on searching Turmain’s house the butter was found. Turmain and his apprentice were then committed to Dover gaol where Twyman turned King’s evidence; Turmain was found guilty and sentenced to seven years’ transportation.6,7 During his confinement on the Hulks [floating prisons] Turmain was allowed to work as a shoemaker but one day as he was working ‘two convicts on board came up to his seat and falling into conversation a dispute arose between them when [one] caught hold of Turmain’s pairing knife and instantly stabbed the other which caused his death. Now it was Turmain who turned King’s evidence; the murderer was tried and convicted and Turmain was set free. He returned to Margate and set up shop again.

On the night of the 28 December 1812 the houses of Jacob Sawkins in Union Crescent and William Abbott in Addington Square were broken into and various items of clothing stolen.4 Turmain was suspected of being involved, but at first the Rev Mr Baylay, one of the Cinque Port Magistrates, was reluctant to grant a warrant, ‘so slight was the evidence’ linking Turmain to the robbery. However, Turmain’s ‘bad character’ was such that Baylay finally agreed to a warrant. Turmain’s house was searched and all the stolen property was found. Turmain then tried to turn King’s evidence once again: ‘with great adroitness, he confessed and impeached his accomplice, Edward Herod, believing, no doubt, that without him there was no evidence to convict Herod.’ Herod was arrested ‘by Mr Marsh, a very active Peace Officer, and both the prisoners were placed in separate rooms at Mr Boys’s office; they were examined, but in the presence of many spectators. Herod denied all knowledge of the burglary, and there appeared to be no evidence whatever against him, except from the confession of Turmin; at last, after nearly three hours attention on the part of Mr Baylay, his ingenuity aided by his clerk, produced sufficient evidence for Herod’s committal, and the prisoners were secured for the night. Soon after this, Herod expressed a desire that he might have a private interview with Mr Baylay, Mr John Boys and Mr Sawkins, which was accordingly granted. A voluntary confession is then stated to have been made, together with a disclosure of other great offences, known only to those Gentlemen, which we hope and trust will prove beneficial to the public peace of safety. The characters of the prisoners excited the usual curiosity of the public to behold them, and throngs of people were collected together on the occasion during the whole of the examination.’

Turmain and Herod were committed to Dover gaol and ‘on the 17th February … they were brought to trial at the General Sessions before Thomas Mantell Esq. Mayor and William Kenrick Esq. M. P., Recorder. The prisoners were both found guilty on the clearest evidence and received the awful sentence of death which sentence was passed on them by the Mayor in the most affecting and impressive manner.’ Herod was recommended for mercy and had his sentence commuted to transportation.3,5,8,9 A handbill of the time reported that ‘Turmain’s wife died of a broken heart about a fortnight before his trial came on. His mother and two sisters visited him on February 25th the time he was under sentence of death. Having expressed to see his three children they arrived in Dover on Monday the first instant accompanied by their late mother’s sister. On their interview with their unfortunate father the scene was truly distressing and to the susceptible and feeling mind may be more correctly conceived than it is in the power of the writer to describe’.5

The gallows were duly erected ‘near the first turnpike at the end of the town, on the same spot where the last execution took place about twenty eight years ago’.5 At eleven o’clock on the day of his execution Turmain ‘was taken from the gaol, and placed in a cart fitted for the occasion, accompanied by the Rev Mr Maule, the executioner being seated on the side, two constables on horseback, with others two and two, on foot proceeded it — the cart was followed by a post coach and three post chaises, in which were the Mayor, the Town Clerk and the rest of the Justices . . . On arriving at the fatal tree, after spending a few minutes in prayer, the executioner then proceeded to do his duty . . . About five minutes appeared to have terminated the suffering of the unhappy culprit, and after hanging the usual time his body was cut down, put into a coffin, and carried to the Bone House of St Mary’s Church, and from there was removed for internment at Canterbury. An immense concourse of spectators were assembled to witness this melancholy catastrophe’.10

Two further men, arrested for an attempt to defraud Cobb’s Margate Bank, were executed at Dover in 1817 for passing forged £5 promissory notes.11 At Ramsgate they had bought goods with forged five guinea notes of the Canterbury Bank, and at Deal and Dover they had passed a number of forged five pound notes of the Margate Bank. This was a serious matter for the Margate Bank and one that received Cobb’s direct attention: ‘Mr Cobb, having traced them to Canterbury, immediately followed the coach (Union coach to London, which they had taken from Canterbury) in a chaise and four, and succeeded in taking them into custody at a watering house on the Greenwich Road. There they were taken to Bow street and then to Dover, for final examination’.11 They gave their names as James Johnson and George Williams. They were tried at the Dover Sessions in November 1817 and found guilty, although the Morning Chronicle suggested that there was some mystery about their real identities: ‘From the manner in which their offence was committed, with so little of art, or of disguise, and from the promptness with which they acknowledged their guilt when apprehended, it is evident they were not old offenders; and subsequent circumstances lead us to believe that the names in which they were tried, were merely assumed; and that in point of fact, they were related to two most respectable families resident in London’.12 The Kentish Gazette later reported that their true names were Joseph Bye and Benjamin Smith.13 At their trial ‘every possible pains . . . were taken to conduct their defence with ability, and no expense was spared, if money could have shielded them from the consequences of their crime, to conduct their trial to a favourable issue. The facts, however, were of a nature so conclusive, and the evidence so clear, that no doubt of their guilt remained, and their fate was finally sealed by the verdict of a Jury’.12

At the end of trial ‘Mr. Cobb, the prosecutor, recommended the wretched men to mercy in the most pathetic terms’.12,14 This recommendation was subsequently followed up by petitions signed not only by the prosecutor and by the Grand and Petty Juries, but also by the Recorder, Mayor, and Aldermen of Dover, in their corporate capacities, all praying an extension of the Royal mercy. The petition from Mary Smith, the wife of Benjamin Smith, alias George Williams, explained the sad background to the crime. Smith and Bye were map engravers working in London. Having heard that engravers could earn good money in Lisbon they set out for Portugal but their ship was seized by a French privateer and they were imprisoned in France for four years until peace was declared between England and France in 1814. On returning to England they managed to get jobs with W.D. Lizars, book sellers and map engravers of Edinburgh, but as journeymen rather than as engravers. As Mary Smith explained ‘with education superior to the station to which they were reduced, and bred up to much greater comforts and comparative indulgence than their daily earnings could afford, this was a galling state.’ Desperation at their ‘fallen condition’ led them to ‘plunge into criminal enterprise’ in an effort to get money to support their families: Smith had a wife and four children and Bye had an aged father ‘in an infirm and helpless state.’ One of the letters written in support of Smith and Bye said they ‘showed great ingenuity in engraving maps but did not excel in engraving written characters’; unfortunately the ability to engrave written characters was rather important for forging banknotes. The petitions were sent to the Office of the Secretary of State for the Home Department, but the Home Department concluded that there were no grounds for commuting the sentence.12

In due course Smith and Bye were conveyed by coach to ‘the usual place of execution, the centre of two cross roads, near the Black Horse public house, at the entrance to the town [of Dover], where the gallows was erected.’ They were attended by the Mayor and other Officers of the Peace and at ‘a quarter before eleven o’clock . . . they were launched into eternity, at which moment a general groan escaped the surrounding multitude, which was immense.’ Then ‘after hanging the usual time, their bodies were cut down and put into coffins, which had been brought with them in a wagon, and conveyed to the church for internment that day’.15

By the 1830s, cases likely to result in a capital sentence were heard at the County Assizes in Maidstone rather than at Dover and those found guilty were executed in Maidstone gaol.2 Some particularly important cases from the Dover jurisdiction were tried at Maidstone even earlier than this. In 1798 five Irish men, suspected of treason, were arrested at Margate by Bow Street Runners, as described in Section 1. They were tried at Maidstone Assizes but one, Coigly (or Coigley, Quigley, or O’Coigly), questioned whether or not this was legitimate: ‘The offence of which he stood accused, he said, was stated to have been committed at Margate, which being situated in the jurisdiction of the Cinque Ports, the charge was not cognized by the Courts of Kent; but, as he had ever entertained the highest opinion of the character of an English Jury, he should wave all objection upon this score of form, and suffer himself to be tried by a Jury of the county of Kent’.16 Nevertheless he was found guilty and sentenced to death. A pamphlet of the time describes how he was drawn on a hurdle to Penenden Heath for his execution:17

he had no hat on, he was without a neckcloth, and his shirt collar was open. The day was extremely sultry, he had been half an hour in coming from the prison, and the trampling of the horses that drew the hurdle, and of the soldiers and multitude that surrounded it, had kept him covered with clouds of dust; and he appeared faint from these causes. A chain which confined him on his seat in the hurdle was taken away . . . He now flopped out of the hurdle, and his friend offered him a piece of the orange which he took; and having eaten it, he bade him farewell. He walked up to the gaoler, who was on horseback at a few paces distant, and said, "Mr Watson, farewell! God bless you! Your conduct to me has been very kind and generous, and I thank you for the many civilities you have shewn me. — God bless you!" He shook hands with Mr Watson; and then ascended the ladder with unshaken courage. As the executioner prepared the rope, the man said something that was probably an apology, for Mr Coigly answered, "Say nothing; you know you must do your duty." The executioner, when he was about to put the rope over his head, said, “You must turn your back, sir." — Mr Coigly bowed, and turned round.

The rope having been placed round his neck and ‘fastened to the tree, and his arms bound behind,’ he addressed the crowd, proclaiming his innocence.

His manner was impassioned, but distant from all extravagance. Having concluded, he said, "I am ready;" but the rope had got out of its place, and the executioner had again to adjust it. During this time, Mr Coigly's countenance was expressive of peace within. While the cap was drawing over his face, he made signs to his friend to approach nearer, and bowing dropped his handkerchief at his feet. That most trying space of time between the moment when the cap was drawn over his face and the falling of the platform, was longer than is usual; during all this time no trepidation could be discovered in his limbs or muscles. His lips moved, and his hands were lifted up in prayer, to the last moment. He died apparently with little suffering. The spectators behaved with great respect toward him. When he declared his innocence, a buzz of applause ran through the multitude, and there was even some clapping of hands. Toward the close of his address, many of the spectators wept, and some of the soldiers were unable to repress their tears.

An important court case arising from the battle of Marsh Bay between the North Kent gang of smugglers and the Coast Blockade Service in the small hours of Sunday 2 September 1821 at Marsh Bay in Westgate also ended in executions on Penenden Heath [see 12. Marsh bay and James Taylor]. The case was heard at the Spring Assizes in Maidstone in March 1822 and of the nineteen smugglers tried, four, Daniel Fagg, John Meredith, Edward Rolfe and John Wilsden, were sentenced to death, but for fifteen others the sentences were commuted to transportation to Van Diemen’s Land, as Tasmania was then called, for between 7 and 15 years. On Monday, 22 April 1822 the four to be executed were taken to Penenden Heath, together with a fifth man John Bell, convicted of burglary. As described in the Kentish Gazette;18

They were conveyed from the gaol soon after eleven o'clock in the forenoon, in the accustomed manner, to the place of execution, where they all conducted themselves with great fortitude and resignation. Bell first addressed the surrounding spectators, warning, young men especially, to avoid the company of abandoned females, by whom he said he had been deluded and betrayed into his present awful situation. The others severally spoke with much firmness; Fagg said that he took the 9s for his night's service for the sake of his wife and family, and did not consider it wrong to be engaged in smuggling; Wilsden solemnly asserted that he had no fire-arms in his possession, Rolfe said that the witness who deposed that he had fired five times had sworn falsely, as he fired only twice; and Meredith declared that he did not fire at any of the blockade men. All, however, declared their cheerful forgiveness of their prosecutors, and hoped that God would do the same. The Executioner having made the necessary preparations, they were launched into eternity, and after hanging the usual time, their bodies were cut down and those of the four latter delivered to their relatives, who were waiting with a wagon near the place of execution.

The bodies were returned to Canterbury for burial in a patch of unconsecrated ground in the yard of St. Mildred's Church.

The last execution to be carried out at Maidstone was for a crime committed in Margate. On Tuesday, 8 April 1930, 31 year old Sidney Fox was hanged for the murder of his mother, Rosaline, in October 1929.19 Fox had a criminal record for offences of theft and obtaining money and goods by deception and he and his mother were in the habit of taking holidays together, leaving without paying their hotel bills. Rosaline had taken out a life insurance policy on her own life and Sidney had also taken out a short term policy on her. Both policies were set to expire on 22 October 1929, while mother and son were enjoying one of their holidays, this time at the Hotel Metropole in Margate. At 11.40 pm on the evening of the 22nd, Sidney raised the fire alarm and hotel staff rushed to his mother's room which was full of smoke. They pulled Mrs Fox out but she was dead, apparently from smoke inhalation. Sidney, as usual, left the hotel without paying the bill and was arrested for this offence a few days later. The insurers were suspicious about his mother's death and reported their suspicions to the police who obtained a warrant to have her body exhumed. When it was carefully examined, the actual cause of death was found to be strangulation. It was also determined that the fire had been started deliberately. Fox was tried at Lewes Assizes and returned to Maidstone to await his execution. After 1930 all prisoners condemned to death in Kent were executed at Wandsworth prison in London.

An alternative to execution for prisoners found guilty of a felony after 1718 was transportation to the American Colonies. Although this was no longer possible after the American War of Independence, an Act of 1776 provided for convicts who would have been transported to be housed in old warships converted into floating prisons known as ‘hulks.’ These were located on the Thames near Woolwich and at Gosport, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Chatham and Sheerness. The hulks were said to be ‘of all the places of confinement that British history records . . . apparently the most brutalizing, the most demoralising and the most horrible’.20 By 1787 the convict settlement of Botany Bay had been established and transportation began again, although the hulks continued to be used to hold convicts before their transportation to the colonies. Transportation to New South Wales was suspended in 1840, to Van Dieman’s Land in 1846, and finally ended to Australia in 1867.

Many men and women from Margate were transported. At the Dover General Sessions in June 1816, William Hayward, a young man of 23, was found guilty of breaking into the house of Frances Singleton, a spinster, and stealing £13 in notes, some cash, and six silver spoons and the Mayor passed the death sentence on him, with a date for the execution of Friday 12 July.21 However, the sentence was then remitted to transportation for life.22 In 1831 Robert Holness,14, and John Bushell, 16, were convicted of breaking and entering the house of James Sinclair and stealing a gold ring valued at five shillings, a razor valued at sixpence and a pair of scissors valued at three pence, and both were sentenced to death. This was later commuted to seven years transportation.23

A sentence of transportation was often used in cases of theft, even for very minor thefts. At the General Sessions in October 1813, Phoebe Emerson, 18 years old, was found guilty of stealing a cotton gown, valued at 2s, and was sentenced to 7 years transportation.24 In 1833 John Jordan was charged with stealing a silver-keyed flute together with some wine and other items from the house of his master, John Boys, leaving them for sale ‘at a fancy shop.’ He was found guilty and also sentenced to transportation for seven years.25 At the Dover General Sessions held in April 1835 the Recorder addressing the Grand Jury said ‘he was happy to state, that on this occasion the calendar presented an unusually small number of prisoners — the offences were all of a trivial nature’.26 Nevertheless, he still sentenced several Margate men to transportation. William Sturgess, a labourer, was found guilty of stealing a quantity of beans and was sentenced to 7 years transportation. Thomas Jones, a labourer, and William Scott, a blacksmith, were found guilty of stealing three chickens from William Keene in Margate and Jones was sentenced to seven years transportation and Scott was imprisoned for twelve months with hard labour. William Gore, a labourer, found guilty of stealing ‘a quantity of spun yarn’ was lucky to get just 9 months imprisonment with hard labour.

Two cases of theft from Sackett’s Margate Bank also resulted in transportation. In 1813 John Clayton, passing himself off as a naval lieutenant, tried to obtain money from both Cobb’s and Sackett’s banks with forged letters of credit. Cobb’s would have nothing to do with him, but Sackett’s advanced him £20. The forgery was soon spotted and Clayton was arrested as he boarded a London mail coach. Sackett took pity on Clayton, who was under 20, and did not press for the death penalty. Clayton was sentenced at the Dover General Sessions to transportation for seven years.27,28 A much more serious case for Sackett’s bank was the theft by John Croaker, a loss so serious that it led to the collapse of the bank.29

John Croaker, while still in his early twenties, was appointed chief clerk at Sackett’s Isle of Thanet Bank, having worked previously as a clerk in the Ramsgate Bank run by John Garrett. 29 He was treated generously by Sackett but Sackett’s belief in Croaker was misplaced; while on a trip to London in 1814 Sackett received the news that Croaker had absconded with a large sum of money and that there had been a run on his bank.30 A few weeks later Sackett received a letter from Croaker admitting his ‘folly’ and explaining that he had been speculating in the public funds, buying and selling interest-bearing securities issued by the Government to finance the national debt.30 Sackett immediately consulted his Margate solicitor, John Boys.31 Since Croaker had sent his letter to Sackett from Dover, Sackett and Boys assumed that Croaker would try to escape to Calais with the several thousand pounds worth of unissued bank notes they thought he had stolen from the Bank. Boys sent his managing clerk, John Baker, to Dover, together with a local merchant, Robert Brooke. In Dover, Baker and Brooke contacted the local banking firm of Fector and Minet, a company with close contacts with Calais. Baker and Brooke were introduced to a French-speaking mariner, William Keys, and all three men then crossed to Calais and toured the lodging houses trying to find Croaker, eventually finding him in the Kingstone Hotel. Brooke, who would have been known to Croaker, urged him to return ‘for the sake of his wife and two infants’.31 According to an affidavit sworn by Keys, Brooke said ‘he was fully authorized to say that if the said John Croaker would give up the property and paper about his person and return to England, matters should be quietly settled and adjusted and the said John Croaker might rest assured no harm should happen to him’. Keys went on to say in his affidavit that he was ‘fully of the opinion the said John Croaker complied with the wishes of the said Robert Brooke and gave up the said papers and notes and promised to return to England upon the faith of the said assurance of the said Robert Brooke that no harm should happen to the said John Croaker’. John Baker also swore an affidavit describing events in the same words used by Keys.

Having accepted Brooke’s promise, Croaker returned to Margate on 22 January 1815 together with his escort and appeared before the Rev W. E. Bayley, one of the local magistrates.31 Boys, who, as well as acting for Sackett, was the clerk to the magistrates, took Croaker into his house overnight, presumably because Croaker had not yet been charged or even arrested. Over the next two days Croaker and Sackett argued their cases before the magistrates and Croaker was persuaded to surrender freehold and leasehold property that he owned to two friends of Sackett, John and Thomas Garrett, who were to act as trustees for Sackett in case any further discrepancies were found in the bank’s books.

Croaker was then formally charged with having embezzled upwards of £1000 from the Bank and was committed overnight to the London Hotel, in the charge of one of the Margate constables. The following day Croaker was moved from the relative luxury of the London Hotel to the gaol in Dover Castle and committed for trial at the next General Sessions.32 Rather jumping the gun John Boys placed advertisements in the local newspapers addressed to ‘any persons owing money to Croaker,’ describing Croaker as ‘late managing Clerk in the Banking-House of Sackett and Co., Margate, and now a prisoner in Dover gaol, charged on the oath of John Sackett, on a violent suspicion of having embezzled and secreted divers Bank Notes, of the value of one thousand pounds and upwards, the property of the said Sackett and Co’.33 He then instructed ‘all persons having possession of any Bank Notes, Exchequer Bills, or any other effects of the said John Croaker, that the same are not to be paid over or delivered up to him, or to any person by his order . . . but they are desired to give notice thereof immediately to me, as Solicitor and Agent’.33

A commonly used legal procedure to obtain a prisoner’s release on bail before a case came to trial was to apply for a writ of habeas corpus. Croaker’s wife Susannah and some of his friends applied for such a writ on 13 February 1815,34 but things moved slowly. The Court of the King’s Bench in London sent a writ of certiorari to the Margate magistrates to establish the facts of the committal but it was not actually until 25 April that the writ was returned, together with the ‘body’ of the prisoner, to the judges. There the judges, under Lord Ellenborough reviewed the evidence and listened to the depositions of John Sackett, Robert Brooke, John Baker, and one Robert Baker.32,35,36 At this hearing Sackett claimed that the fraud amounted to £3000 and Brooke claimed that, when in Calais, Croaker had offered to return all the money he had with him and to reveal the whereabouts of the rest of the money, as long as Sackett agreed not to press charges against him.32,37 Council for Croaker pressed for a discharge on the grounds that it was not possible to prove that the money recovered from Croaker in Calais actually was the property of Sackett. In case this line of argument failed, the defence also pressed for bail on the purely technical grounds that the warrant of detainer had described Croaker as having ‘embezzled’ the money rather than having ‘feloniously embezzled’ it, the difference being that as a mere embezzler he could get bail. Council argued that this was particularly important ‘on account of the length of time which elapsed between Sessions at the Cinque Ports, there seldom being more than one Sessions in the year, and sometimes not that; in fact, fourteen months had elapsed between the last Sessions and the Sessions proceeding.’ The judge, however, agreed with the prosecutor that omission of the word ‘feloniously’ made no difference and that the seriousness of the case was such that bail was inappropriate. The Court did, however, ask when the next sessions at Dover was likely to be held, and were told that ‘the Justices had determined to hold the Sessions next month, and to hold them in future at regular periods, and more frequently than formerly.’ Croaker was therefore returned to Dover gaol.

The Magistrates, presumably keen to be seen to be keeping their promise, did indeed hold a Sessions at the end of May, but Croaker appeared at this Sessions not on the charge of embezzling Sackett’s Bank, but on a new charge of embezzling a cheque for £10 13s paid into Sackett’s bank by Hunter, a Margate brewer. Council for Croaker argued that Croaker had not been given the required two days notice of this new charge, and had therefore not been able to prepare his defence.38 The Council for the prosecution admitted that the customary two days had not been given ‘and regretted that it had not been done in this instance.’ The Court agreed to postpone the case and ordered a further Sessions to be held on 18 October when Croaker could be tried on the original charge.38

On 18 October a Sessions was duly held at Dover where Croaker was tried before the Recorder for Dover, Mr Kenrick, on the main charge of embezzling £3000 in Exchequer bills from Sackett’s bank. It had also been intended to try Croaker for forgery, a charge that carried the death penalty, but the grand jury failed to accept the indictment. 30 The defence was conducted by John Gurney, a skilful barrister later to become a judge, with Croaker presenting his side of the case ‘in a very collected manner, and at some length.’ Three friends testified for Croaker as character witnesses, including John Garrett, his former employer in the Ramsgate Bank, and Benjamin Kidman, a Margate wine merchant running a business in Hawley Square. After retiring for just fifteen minutes the jury returned with a verdict of guilty.

Croaker had a last opportunity to address the court before sentence was passed by Kenrick. Croaker repeated his complaint that he had fulfilled his part of the agreement made in Calais to give up the money he had on him in Calais, but that Sackett had not kept his part of the bargain. In his summing up Kenrick clearly believed Croaker’s story about his arrangement with Sackett but argued that Sackett was wrong to have made such an arrangement; ‘However disreputable the promises made might be, it was the duty of the parties to prosecute; it was a duty they owed to their country, and most likely if they had not prosecuted, they would have been prosecuted in their turn, for not prosecuting.' Kenrick felt that ‘the extent of the crime in this case, as well as its intricacy, proved that artfulness was not wanting in the prisoner,’ but nevertheless, he also believed that Croaker’s co-operation should not be overlooked. The trial ended in a bizarre confusion about the sentence. Although 14 years transportation was the norm for such an offence, Kenrick was understood by the reporter from the Kentish Gazette to have passed the following sentence on Croaker 'That you be transported beyond the Sea to New South Wales, or as the Privy Council will direct, for the term of seven years'.30 The Kentish Chronicle, however, reported that the sentence was for 14 years transportation.39 and on 24 October the Kentish Gazette printed an apology, stating that its reporter had made an error and that the sentence was indeed for fourteen years.40

As was usual, Croaker rapidly prepared an appeal to the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth, against the sentence.31 In his petition Croaker reiterated the argument that he had assigned his property to the Garretts in trust for Sackett and had been given assurances that Sackett would not prosecute. This was joined with the affidavits from John Baker and William Keys already mentioned and a plea from his wife Susannah, urging the return of ‘my birthright and my children’s hope’ and saying that ‘a great breach of faith [was] made by the Prosecutor’. Lord Sidmouth did not consider the papers until February 1816 but, finding some merit in the case, he then presented it to the Prince Regent.41 The case was then passed to Kenrick for review and, if he thought it justified, to make a recommendation for the exercise of the royal prerogative. Unfortunately for Croaker, Kenrick reported that the appeal had no merit, that Sackett’s promises were largely irrelevant, that Croaker had been consistently cheating Sackett, and that the law should take its course.31 Croaker’s appeal was rejected.

After his trial, Croaker was sent to the hulk Retribution at Sheerness and on 12 May 1816 was transferred to the Mariner for the journey to the penal colony of New South Wales. His wife Susannah and their two children were given permission to join him in New South Wales and, in mid May, sailed in the ship Elizabeth, actually arriving in Sydney Cove on 12 October, a few days before Croaker arrived.29 Initially Croaker did well. He was soon found employment as a clerk in the government offices, and then joined the Bank of New South Wales and helped to establish one of the colony’s first malthouses, but a combination of bad luck and poor timing led to increasing debt. In 1823, having obtained a free pardon, he decided to return to England. Unfortunately the ship he chose for his return voyage, the Mariner (not the Mariner in which he travelled out) was not seaworthy and seems to have gone down on the coast of Chile; no more is heard of Croaker. His widow remained in New South Wales, remarried, opened a school, and died in 1866, aged 76, leaving a large family and a considerable estate.29

|

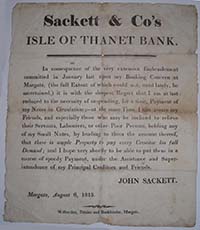

Figure 1. Poster announcing that Sackett & Co’s Isle of Thanet Bank had stopped payment. August 6, 1815. [Margate Museum] |

The case proved fatal for Sackett’s Bank. On 6 August 1815 Sackett had announced that the Isle of Thanet Bank had stopped payment ‘in consequence of the very extensive embezzlement’ of money and that he could no longer honour his bank notes.42,43 This allowed the Cobbs to take over Sackett’s Isle of Thanet Bank and so to exercise a monopoly in Margate banking for many years to come.29

Most criminals, of course, did not bring down banks; most crimes were rather petty and often driven by poverty, but the punishments handed out to petty offenders seem to us now to have been very harsh. In 1773, two Margate brothers, John and Jacob Stamper, were sentenced to be publicly whipped in the Market Place at Dover for stealing beef from the stall of William Rooks, a butcher.44 In 1807 Benjamin Cowell was imprisoned for three months and publicly whipped, for stealing three pounds of salt beef from Thomas Darly, of Margate.45 Similarly, Henry Muller (or Mullett) was ordered to be publicly whipped having been found guilty of stealing a quantity of soft sugar from a warehouse belonging to Nathan Solomon, of Margate.46,47 At the Dover General Sessions in June 1816 Edward Price was found guilty of stealing 7 yards of flannel from the house of Joseph Hollams and was sentenced to 3 months imprisonment in Dover gaol and ‘to be publicly whipped at Margate’.48 In 1836, Thomas Emptage, a 12 year old sweep, was charged with stealing two loaves of bread. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced to ‘one week solitary confinement, and to be once privately whipped’.49 In 1838 another young boy, William Watler, just 12 years old, pleaded guilty to stealing 1s 1d from the house of James Brice, in Margate. His father was called at his trial as a witness but, being put in the witness box, was found to be ‘in such a state of intoxication that he was not capable of articulation.’ The Recorder was sympathetic: ‘[he] addressed the boy and told him that he must take care of his conduct in future for if he came before the Court again he would be sent out of the country, and if he was to continue with the kind of conduct he had begun, he might some day come to the gallows.’ But sympathy then was not the same as now: the Recorder sentenced him ‘to seven days solitary confinement, after which [he was] to be well whipped and discharged’.50

The pillory was used for more serious public offences such as fraud and some sexual offences. A prisoner in the pillory stood with his head and hands fixed in a wooden bar, often with his offence written on a paper label displayed above his head. If the crowd watching the spectacle were in an angry mood he could be stoned, often receiving serious injury. William Morgan, ‘a miscreant from London’ had been found guilty ‘of an attempt to commit an unnatural crime on the body of John Cobb, a young lad of Margate,’ and was sentenced to be imprisoned for six months in the gaol at Dover, and ‘to stand one hour in the pillory, at Margate’.51,52 This punishment duly took place one Saturday at the Fort in Margate ‘when he was pelted with filth of every description by the populace assembled to witness the exposure of the miscreant.’

A rare pamphlet written by a Margate linen draper, a Mr Savill, describes the whole experience of being in a pillory in graphic detail.53 Savill was accused by Sarah Bayly of sexually assaulting her six year old daughter Mary at his house in Margate where Mary had stayed over the night of 28 December, 1799. Although Dr Silver, who had examined Mary on 29 December, was unable to say whether or not Mary had been sexually assaulted, Sarah Bayly obtained a warrant for Savill’s arrest and on 31 December Savill, who was at a Custom House sale in Dover, was duly arrested and taken before the Mayor and the Town Clerk of Dover who, having heard what Sarah Bayly had to say, committed him to gaol. The following day Sarah Bayly returned to Margate to obtain evidence against Savill, while Savill’s housekeeper was collecting information for his defence. Meanwhile, as the mayor had refused him bail, Savill remained in Dover gaol until his trial at the next General Sessions which was not finally held until 7 June 1800. This long period of pre-trial imprisonment created severe financial problems for Savill. As a linen-draper he rented a house and shop in Margate, at £38 per year, and in the winter travelled ‘to the manufacturing towns, to buy and sell goods, as a wholesale dealer.’ For the winter of 1799/1800 he was of course unable to trade in this way and claimed that as a result he had lost several hundred pounds. During this time, in his own words, he was:

kept locked up in a close confined cell, night and day, tainted with a privy, and almost poisoned with all manner of other filth and vermin, and surrounded with a quantity of game-cocks, hens, and chickens, in the yard, and in the cells of the prison, that, between them and swarms of flees, lice, rats and mice, making such a lumber in the night, and crowing in the morning, it has been impossible to rest for them altogether in bed; and friends have not been permitted to come to give me assistance, in a lawful manner, about any kind of business whatsoever — Not even to keep me sweet and clean, neither for love nor money, except one who could swear to my innocence — and she was only suffered to put my meals through the wicket of my cell-door, which was only 7 inches by 8; and, to do that, she has undergone great trouble and difficulty, in many instances, through Harris's [the gaol keeper] threats and ill-usage, — such as dashing her on the floor, bruising her in the face and eyes, by which she was in fear, and in danger of her life, without any just cause; and, in consequence, was overwhelmed with grief — which has been too much for her tender feelings, as well as mine; and she often told me, that she must decline attending of me, not being able to bear the abuse she so frequently received from Harris; but, as I know I must be a lost man if she left me, with strong persuasions, she continued to attend me, no other person being permitted.

The one woman who was allowed to visit Savill was his house keeper, who ‘has gone under the denomination of my wife, though she is not.’ This misunderstanding was potentially important for Savill since a wife was not allowed to give evidence at the trial of her husband, but a housekeeper, not being his lawful wife, could help in his defence.

At his trial Sarah Bayly again accused him of sexually assaulting her daughter and Dr Silver was again unable to say whether or not an assault had actually taken place. Savill called his house-keeper as a witness to say that he could not have committed the assault of which he had been accused as he ‘slept by the side of a woman, of about twenty-three [his house keeper], the whole night and was never left alone with the child.’ Savill’s contention was that Sarah Bayly had brought the accusation in order to get money from him ‘as she was often complaining . . . that she found very hard work to live upon her husband’s weekly pay:’ her husband was a journeyman blacksmith. Indeed, Savill reported that ‘the child acknowledged in court, that her mother told her to say what she did, and her father would buy her a doll.’ Nevertheless, the jury found him guilty and the recorder passed the sentence: ’To be imprisoned one calendar month, and within that time to stand in the Pillory in the Market Place, Dover.’

|

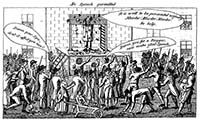

Figure 2. Savill in the pillory at Dover, 1800. [from The Case and Trial of Mr Savill, Dover Corporation Laws Made known to the Lovers of Justice, Printed by A. Young, London, 1800.] |

After the trial Savill’s treatment in the gaol worsened: ‘I was then put down, and close confined, with strong double doors, in one of the lower cells, where I was still more disturbed with a numerous vermine of rats, &c, having been frequently obliged to get up in the night, to kill them. It has been Harris's policy, to try every means to keep all friends from me that could be evidence against him . . . Harris's conduct to me has been most desperately wicked, and too much for flesh and blood to bear.’ On the 28 June Savill was put in the pillory at Dover. This was:

fixed up against the side of a building, facing the spectators, (supposed to be between three and four thousand,) and could not move round in the manner pillories commonly do. I was pelted at in a most shameful manner, and afterwards was informed that Mantell, Mayor, and King, Deputy Mayor, stood and laughed at the sight. I had no other reason but to believe the Mayor and King were determined that I should be murdered, if they could have done it genteelly, and afterwards brought it in accidental, having upwards of forty constables under a kind cloak of deception. About eight or ten of the ignorant seafaring, and blackguard ruffians, who knew not what they were about, were admitted into the circle, close to the pillory, to pelt me with stones and all manner of filth; and one of the villains even came up and took the filth from under my feet several times, without any interruption by the magistrates or constables, when they might have been prevented with ease. I was used in such a manner, that I expected nothing but death; many of the spectators thinking the same, cried out open shame, and said that I should be a murdered man. One man, to a certainty, fainted away at the sight; others said it was worse than murder, and if the corporation wished to murder me, why did they not blow my brains out at once. My face and head were cut in a most shocking manner. The blood flow'd from my head and temples as though I had been stuck with a knife, through which I was quite blind of one eye for several days, and my friends who saw me did not expect my recovery. I cannot express bad enough the cruelty I experienced — but it was from the mercy of God, my spirit and constitution, I am still alive — and not from the mercy of Mansell and King, who made themselves masters of this infamous conduct, being determined to shew their great power, ambition, and authority, because I had before told them to their faces, and by several letters, of their duty and misconduct towards me; and now I have told them more, and will still tell them more yet, as I am not afraid of man in this case; and I never will bend to my enemies — for before I would, I would suffer death unjustly knowing my innocence. I hope, for the time to come, Mantell and King will know better how to do justice, and no more act upon such arbitrary principles, contrary to law, justice, and reason.

Unfortunately the case seems not to have been reported in any of the local or national newspapers so that we only have Savill’s side of the case. What is clear, however, is the ability of the Mayor in such cases to wield great power over the accused and, if he wished, to ‘ruin and distress a man’ as claimed by Savill in his pamphlet.

For less serious crimes such as petty theft, vagrancy and drunkenness prisoners were put in the stocks, with their heads, ankles and wrists locked in a frame. The use of the stocks in Margate had largely died out by the end of the eighteenth century, but then in 1826 their use underwent a brief and unexplained burst in popularity, with the magistrates at least. A letter from the Rev Frederick Baylay to Francis Cobb, the Deputy, raised a problem about their use after such a long time:54

My Dear Sir

It is absolutely necessary that the Stocks should be removed into some convenient part of the Market Place, as there is a person now liable to be put into them for drunkenness and it would [be] illegal to place him there whilst they are in the Prison.

In 1826, three men, Knock, Sturges and Cooper, were put into the stocks in the Market Place at Margate, for six hours. They had been found guilty of ‘tippling and disorderly conduct on the sabbath day,’ and, having refused to pay a fine, ‘it was deemed proper to enforce the sentence, in hopes it may be a warning to others for the future.’ It was reported that the stocks had not been used at Margate for forty years.55 Having restarted the tradition the magistrates again sentenced ‘two notorious characters’ for six hours in the stocks in July, although they ‘braved it with seeming pleasure to themselves.’ The constables were present to prevent any trouble, and one was reported to be ‘enjoying his pipe during the ceremony’.56 The stocks were again used in November to punish two men, Batt and Pritchard, ‘for refusing to pay a fine levied on them by the Magistrates for drunkenness &c’.57

Finally, when the use of the pillory, stocks and whipping died out, petty offenders were often sentenced to short periods of imprisonment, often with hard labour. In 1834 Edward Knott, who had been found guilty of assaulting one of the Margate constables in an attempt to rescue two prisoners, was sentenced to six months imprisonment and hard labour.58 Thomas Pritchard, a cordwainer, was found guilty of assaulting another of the Margate constables, Charles Mummery, and was sentenced to three months imprisonment with hard labour.59 When Dover gaol was inspected in 1837 it contained, as well as those awaiting trial, four male prisoners sentenced to twelve months imprisonment with hard labour for a range of minor offences, and one female prisoner sentenced to nine months imprisonment.60 The inspector felt that the sentences were ‘apparently very severe,’ although this was mitigated by the fact that there was actually no system for implementing hard labour within the gaol, as described in Section 8, Dover Gaol and Margate Criminals.

It was not unusual for the friends of a prisoner to petition the Home Department for a more lenient sentence. Unsuccessful petitions on behalf of George Williams and James Johnson, sentenced to death for forgery and John Croaker sentenced to transportation for embezzling £3000 from Sackett’s bank have already been described. On a more modest scale, Robert Salter of Margate wrote to Henry Dundas, the Secretary of State for the Home Department, in 1793 on behalf of William Davis who was in Maidstone Gaol having been sentenced to six months imprisonment for passing a counterfeit shilling coin.61 Salter suggested that Davis should be released from jail and sent on board a Man of War, since Davis was a qualified seaman and ‘would gladly embrace his Majesty’s Service’ and since this would ‘administer the greatest comfort to his afflicted parents who are good people.’ Unfortunately, despite two letters, nothing seems to have been done for Davis.

In some cases petitions were successful. At the Dover General Session in July 1838 Henry Johnson and Stephen Young were charged with stealing a hat and after hearing the summing up of the Recorder, the jury ‘after consulting a few minutes’ found them both guilty.62 However, before sentence was passed, a Margate man, John Young, ‘stepped forward and said, he had known the prisoner Johnson, for eight years, and had always known him to bear an excellent character for honesty.’ The Recorder declared that ‘Johnson should have the advantage of his good character, and therefore he would subject him only to imprisonment for six months.’ The Recorder had a very different message for Stephen Young, saying that ‘he had been cautioned at last sessions, when he appeared as Queen’s evidence in a case of theft, that, if he again came before the Court, he would be transported beyond seas, and now that he had been convicted of felony, he [the Recorder] must take this course.’ Young was therefore sentenced to seven years’ transportation.62 However, in September it was reported that a petition on behalf of Young ‘has received favourable attention of Lord John Russell, and the sentence has been commuted to imprisonment in the penitentiary. The family of Young are of very good character, and we understand that the greatest exertions in their behalf, have been made by our worthy Deputy, Mr Cobb’.63

By 1843 it seems to have been expected that sentences of transportation would not be carried out. In that year James Collins, a boy of 12, was charged with stealing a watch and offering it for sale to John Fagg, a watchmaker in Margate for 2s.64 Collins told Fagg that the watch belonged to his father, but Fagg did not believe him and said his father should come to the shop. Collins returned in 15 minutes and said ‘his father was too tired to come.’ As Fagg thought the watch was worth about 25s he guessed that it must have been stolen and so he gave it to S. C. Marchant, the superintendent of police. Marchant went to Collins’ home and accused him of stealing the watch; Collins first said that the watch had been stolen by Will Joy while he just kept watch, but afterwards, before the magistrates, he admitted that Joy had had nothing to do with it, and that he had stolen the watch. The Jury found Collins guilty and Marchant then reported that Collins had twice before been in custody for felony, and on the last occasion was sentenced to 3 months’ imprisonment. Then ‘the Recorder said, as imprisonment appeared to have no effect, he considered it his duty to pass a sentence of “seven years transportation,” not with a view that it should be carried out, but that the Government might send him to some establishment, where he would, if he behaved properly, be taught some useful trade.’

The courts themselves could also, of course, show leniency. At the General Sessions in April 1834 Henry Cobb was convicted of stealing three pairs of shoes from outside the shop of Thomas Dunn. Dunn, although he brought the prosecution against Cobb, ‘expressed regret that it had fallen to his lot to appear against the prisoner, and begged to recommend him to the merciful consideration of the court, from a conviction that he had been led to the offences in a moment of destitution.’ As a result Cobb was sentenced to just two months imprisonment with hard labour.65 At the same time however, the powers that be felt that there was too much general misbehaviour and too much low-level crime in the town, largely due to gangs of poor boys hanging about in the streets. When the new Market building was completed in 1821 and the Improvement Commissioners came to write the regulations for the Market, they were careful to include the following as the sixth regulation:66

That with a view of preventing boys or other persons from committing nuisances, either by cutting, or in any way defacing the stalls, or any part of the Market, or by rioting, hallooing , or in any way incommoding the public within the Market, Robert Harty be appointed with a salary of 5s per week and a reward of 5s for the detection of every offender.

In 1837 when the Margate Constables were being sworn in, they were advised to ‘take care to caution and keep their eyes upon all idle boys in the street’.67 In 1838 the Milton and Gravesend Journal complained of a group of ‘low lazy vagabonds . . . assembled around the Post Office to insult all those who went to collect letters’.68 They added: ‘such an outrage would not have happened in Ramsgate, where the inhabitants are protected by an efficient and respectable police.’ The first decision of the Watch Committee established in 1858 to supervise the Margate Borough Police was to order the police superintendent to station one of his constables outside Trinity Church each Sunday between 7 and 8 pm, to 'preserve order among unruly boys’.69

These worries about the youth of Margate are supported by the court records. In January 1832, four of a gang of young offenders, Richard Nash, William Goldfinch, Stephen Smithers and George Smithers were committed to Dover gaol to await trial on the capital charge of burglary, breaking and entering the shop window of the house of Samuel Whynne, at three in the morning and stealing money and other property.70-72 The Kentish Gazette fumigated ‘If parents of poor children will send their offspring forth early and late, with empty bags, to collect potatoes, or turnips, or firewood from fields and hedges – or coals, or in short anything they can lay their hands upon (which is said to have been notoriously the case in this place), it cannot be wondered at, that as the child grows up he will not depart from [these] habits . . . the Margate constables assert, that there is a gang of from ten to twenty boys under 15 years of age in this place, who congregate and are organized as effectually as any London thieves.’ The answer, suggested the Kentish Gazette, was corporal punishment.70 The first three of the youths had been previously convicted of felony, and all were sentenced to death, although by 1832 the sentence would have been commuted.

At the Dover General Sessions in April 1834, two youths John Legg [or Legge], aged 15, and George Holliday, aged 14, were indicted for stealing 18s 6d and a wooden drawer from the house of John Pettit, at Margate having been found with the money in their possession.73They were found guilty ‘but strongly recommended to mercy on account of their youth, and the bad example under which Holliday, in particular, had been brought up, his father having been transported.’ They were sentenced to three 3 months imprisonment with hard labour. Unfortunately this story did not have a happy ending. At the end of his sentence Holliday ‘was discharged with a small pecuniary assistance, and advised to make the best of his way home’.74 But within a week he was committed to Dover gaol charged with having broken into No. 4 Fort Paragon and stolen a purse containing 6s 6d. At the summer General Sessions he was found guilty and sentenced to transportation for 7 years.75 John Legg’s story was equally unhappy. At the Dover General Sessions in July 1835 he was convicted of stealing a pair of barrel steel-yards and a knife and because of his previous conviction he was also sentenced to transportation for 7 years.76 The Dover Telegraph reported that ‘His mother and sister, on hearing this, lavished the most indecent abuse on the Recorder and Jury, and were forcibly removed from the Court by the Constables.’

In 1836 George Kemp and John Bax, both just 10 years old, were charged with breaking into the house of William George Mussared, a fish monger in Hawley Square, and stealing some shrimps.77,78 They were sentenced to 14 days imprisonment; the Dover Telegraph reported ‘they appeared to have no friends. A sea-faring man named Wilkens, who said he walked from Margate to speak for Bax, whom he had brought up, promised to take them back after their release’.77

In 1844 James Gardner and Fuller Duff, two youths aged 15, were charged at the Spring Quarter Sessions with stealing 22 yards of rope from James Webb.79 The jury found them not guilty on the grounds that there was no direct proof that the rope found on Gardner and Duff was that lost by Webb. Nevertheless, when the Recorder asked Inspector Marchant ‘what character the lads bore,’ Marchant replied ‘very bad.’ He reported that ‘they were half-brothers, and, unfortunately, from the quarrelling of their parents, the lads were almost deserted, and allowed to subsist on plunder. They usually slept in a barn, and on searching which he found bones of ducks and poultry. They had once been in custody for stealing a ring, but the parties declined to prosecute.’ Finally the boys were discharged, ‘after a severe reprimand from the learned Recorder’ who clearly thought they were guilty and had been lucky to get off. Again the story does not have a happy ending. At the December Sessions the same year, Fuller Duff was again before the court this time accused of stealing a duck, the property of Thomas Town; earlier he had been seen throwing stones at the ducks in Thomas Town’s pond.80 This time Duff was found guilty, and Inspector Marchant reported that this was the fourth time he had been in custody in the last year on charges of felony. The Recorder said that ‘but for the unfortunate circumstances connected with the prisoner, and the late changes in the law on transportation, he would have been transported;’ instead he was sentenced to six months imprisonment with hard labour.

In 1857 Henry Whitnall, claiming to be just 12 years old but probably older, came before the local magistrates at Margate but, because of his record, they committed him to Dover gaol for trial with the hope that he might be sent ‘to some reformatory establishment’.81 At the Dover sessions he was found guilty of stealing a pair of copper scales, worth 2s, and also pleaded guilty to two previous convictions.82,83 He was reported to be ‘totally devoid of education’ and Superintendent Marchant said he had been in his custody nine times for various petty offences, and had been committed to prison on six previous occasions:

December 1854 |

Stealing bottles, sentenced to seven days imprisonment and once whipped |

January 1855 |

Stealing six iron bars, sentenced to six weeks imprisonment and once whipped |

April 1855 |

Sentenced as a rogue and vagabond to three months imprisonment. |

April 1856 |

Stealing a shirt [or night dress], sentenced to one months imprisonment |

August 1856 |

Stealing a fowl, sentenced to three months imprisonment and once whipped |

On the first of these occasions, in 1854, Henry Whitnall was one of three boys, all under 12, who were charged at the Margate Petty Sessions with stealing 8 glass bottles from the wine merchant, F. Abbott, in Cecil Square.84 The boys confessed that they had stolen bottles on previous occasions and were sentenced, under the Juvenile Offenders Act, to seven days’ imprisonment and ‘to be once privately whipped.’ According to the South Eastern Gazette when Whitnall was committed for stealing a night dress in April 1856 it was the fifth time he had been committed in the last 12 months.85 At his trial in Dover in 1857 the recorder observed that he was ‘evidently a very bad boy’ and sent him to Dover gaol for one month and then to reformatory at Redhill for three years.83

Another serial offender was Edward Price. In 1833 he was tried at the Dover sessions with George Austin and Robert Davison for breaking into the house of James Pullen at Margate and stealing a watch and other articles, but the Jury found ‘not a true bill’.86 The same happened when, aged 16, he was tried at the Dover General Sessions in April 1834, again with George Austen, 16, and Robert Davison, 19, for stealing a loaf of bread.87 The Dover Telegraph reported: ‘The Prisoner Price, who is known as a leader of the juvenile thieves that infest [Margate], has been four times examined before the magistrates there, on charges of burglary or felony, and was tried and acquitted of the latter, at the sessions last summer’.87 He was less lucky in 1836 when, with John Cowell and James Dennis, he was convicted of stealing two bushels of potatoes from Mr Curling, the master of the workhouse at Margate.88,89 This time he was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months imprisonment with hard labour; Cowell and Dennis each got 3 months hard labour. Finally, in 1838, with Frederick Hewitt he was found guilty of stealing four trusses of hay from Hills Rowe at Margate.90 Hewitt was sentenced to 9 months imprisonment but Price was sentenced to transportation for seven years. On 25 June 1838 he was sent on board the Coromandel to Van Diemen’s Land. The Death Register for New South Wales shows an Edward Price as being shot dead on 12 November 1839 while attempting to escape from the charge of Corporal Wade.91

Even the local justices seemed to accept that the farm land surrounding Margate was a temptation for those going hungry; in answer to a question from the Royal Commission on the Constabulary in 1839 as to whether there were any ‘peculiar facilities or inducements to commit crime’ in the neighbourhood, they replied ‘none, except such as are common to unenclosed land, viz stealing of turnips and potatoes.’92 In 1838 three men, William Sticketts and brothers Edward Sharpe Pritchard and Vincent Andrew Pritchard were tried at the Summer Sessions at Dover for the theft of five bushels of wheat from Mr Finnis’s farm at Salmstone, where they were working.93 The jury, after an hour’s deliberation found Sticketts guilty and he was sentenced to seven years transportation. The Pritchard brothers, were, however, acquitted, ‘on some informality’.94 The Pritchards were less lucky the following year when, together with John Goldfinch, they stole two sacks of peas from the same farm.95 Early one morning in January 1839 a man called Holley, a wagoner, was driving into Margate when he met Vincent Andrew Pritchard on the road. Pritchard asked him if he would take a load for him into Margate. He agreed, and John Goldfinch and Edward Pritchard then emerged from a gap in the hedge and put two sacks into his cart. He took them as far as White’s place, where Edward Pritchard lived, and where Goldfinch and the two Pritchard’s unloaded the two sacks. In the subsequent court case, Inspector Marchant reported that:95

from information, he went to watch a house in White’s place, where he concealed himself with policeman Solley. [Edward Pritchard] shortly came up, and turned into a yard leading to his house, and he heard a door unlocked. [Edward Pritchard] came back, and after looking cautiously down the high street, gave a signal to Goldfinch and [Vincent Andrew Pritchard] came up with two sacks. [He] and Solley then rushed out and captured Vincent Pritchard and Goldfinch, but [Edward Pritchard] escaped.

Vincent Andrew Pritchard and John Goldfinch were taken to the Margate station house and Mr Marchant then ‘took their boots off; which being very remarkable, he succeeded in tracing across some ploughed fields to Mr Finnis’s farm, at Salmstone, and back again’.96 They were tried at the Margate Petty Sessions before Williamm Nethersole, J. T. Pratt, and the Rev F. Barrow, where Pritchard said he only stole the peas because he was starving. Nevertheless he was committed for trial at the Spring Dover Sessions, where, with Goldfinch, he was subsequently sentenced to seven years transportation.96-98 Vincent Andrew Pritchard was sent to the hulk York at Gosport and then on board the Antelope to Bermuda. After serving his sentence he returned to Margate and his wife and family, working as a labourer and brickmaker, finally dying at the age of 80 of bronchitis; his wife Mercy Ann died in the Union Workhouse at Minster, aged 89, of ‘senile decay’.109

A description of Edward Sharpe Pritchard was published in the local newspapers; he was 30 years old, 5 feet 6 inches tall, ‘stout made, fair complexion, very much freckled, carroty hair and whiskers, which are very full, and was dressed in a dark close body coat, blue cap, and short white smock frock over his coat’.97 He evaded punishment until September 1841 when he was arrested in Dover and tried at the Winter Sessions at Dover at the end of 1841, also being sentenced to seven years transportation.95 He was sent on board the Forfarshire to van Diemen’s Land and is believed to have remained in Australia.109

In 1853 William Ansell, a 21 year old labourer was charged with stealing 12 gallons of potatoes worth 7s from John Birch’s farm at Northdown.99 He had been seen very early one December morning by Edward Young, one of the Margate constables, with a barrow loaded with potatoes. Young asked Ansell where he had got the potatoes and Ansell replied ‘from Garlinge’ to which Young replied that this ‘was a strange way to come from Garlinge!’ and arrested him. Young then set about gathering the information required to obtain a conviction: ‘I afterwards went to Mr Birch’s at Northdown and found a potato clamp had been opened. Footmarks were around and prisoner’s shoes corresponded with the marks — I also traced similar footmarks towards the spot at which I had met prisoner at first.’ Ansell was tried at the Dover Winter Sessions and found guilty. Inspector Marchant reported ‘he knew the prisoner well, having had him eight times in custody — He was an associate of thieves.’ He was sentenced to six months in prison with hard labour.99

Also in 1853 Daniel Shelvey, one of the constables, found a group of four men stealing potatoes:100

I was on duty in the upper part of High street Margate on the night of Tuesday the 15th March last and about ¼ past 11 o’clock saw the prisoner Henry Bishop and three other persons go down Frog Hill which road would lead to Mr Smithetts’ Farm at Hengrove; they had bags with them but I can’t state which of them — I heard one of them say “don’t run, don’t make a noise.” Shortly afterwards I saw my Inspector and, by his directions, I and Police Constable Young placed ourselves on Frog Hill in a position to watch — about one o’clock in the morning the prisoner Bishop accompanied by another of the men came up Frog Hill with a sack on his back containing potatoes — I apprehended the other man [William Simmons] but Bishop threw down his sack and potatoes and made his escape — the sack which Bishop had on his back and afterwards threw down contained one bushel of potatoes.

Bishop was later seen at the top of the High Street by Police Constable Young, and arrested. The following day Shelvey took Simmons’s boots ‘which had nails at the bottom partly loose and the rows of nails imperfect. I went to Mr Smithett’s at Hengrove . . . and went with his Bailiff William Solly to Mr Smithett’s potato bank — Young who was with me compared the boots of Simmons with footmarks near to the bank . . . the footmarks tallied with Simmon’s boots — two rows of nails on the boots are imperfect, the other three are perfect.’ William Solley estimated that about two bushels of potatoes, Jersey Blues, had been taken, with a value of about 6s. Simmons and Bishop were committed for trial at the next Dover Sessions and given bail, by personal recognizances of £20 each with two further sureties each of £10, and at the Dover sessions each was sentenced to 14 days’ hard labour.100,101

In 1834 Richard Pysden, a 25 year old labourer was accused of stealing two chickens from Major Garrett, of the parish of St John’s.102 Westfield, one of the Margate constables, arrested Pysden ‘as he was entering the town, by the Dane, on night of 7 December . . . with the fowls tied up in a gabardine.’ He was found guilty and sentenced to four months imprisonment with hard labour. It was evidently difficult for poor men to resist the temptation of a chicken or three. In April 1835 Thomas Jones, a 21 year old labourer, William Scott, a 19 year old blacksmith, and Thomas Fox, a 29 year old labourer, were accused of stealing three chickens.103 Their mistake was to offer the chickens to Robert Jordan, a poulterer at Margate, at such a low price that Jordan became suspicious and ‘caused the parties to be apprehended.’ The jury found Fox not guilty and both Jones and Scott guilty. Scott was sentenced to 12 months imprisonment with hard labour but Jones was transported for 7 years. The difference in sentences was because Jones had been convicted just the year before for stealing potatoes and had been given the ‘lenient’ sentence of 12 months imprisonment and the court was upset that he had shown himself unworthy of the mercy shown to him last time.103

As always, poverty fell particularly hardly on unmarried mothers. In1839 Mary Massared was found guilty of stealing 14 yards of silk, worth 42s, which she tried to pledge at two pawnbrokers in Margate.104,105 She put in a written petition to the court, ‘imploring for the mercy of the Court’ explaining that she had left home four years previously and gone into service following a disagreement with her father, ‘but having the misfortune to bear a child, now 10 months old, and in the prison with her, she had lost her station.’ Making matters worse, she and the baby became ill, and the money she earned as a shoe-binder was not enough to support them both. She had been refused all parochial relief and was destitute when she stole the silk. The court ‘took pity on her’ and sentenced her to one months imprisonment.

A poignant example of a parent caught in the contradictions of the system is provided by the case of Mary Pevy.106 Pevy, a thirty-year-old unwed mother from Margate, gave birth to a daughter in the Dover Workhouse in 1877. After she and her daughter were released, Pevy look a job as a cook to support herself and the child. This required her to wean the child and leave her with neighbours. Pevy was arrested for abandoning the child and sentenced to three months in jail. While Pevy was in jail the child was kept at the workhouse, where her health improved markedly. Upon her release from prison Pevy begged the authorities to keep the child at the workhouse, as she had no job and no means of caring for it. Her request was denied. She then pawned her clothes to buy corn flour, bread, sugar, and milk to make gruel to feed the child. When that supply ran out she again applied to the workhouse and was again rejected. Pevy said the child was ill, but the workhouse physician said there was no evidence of disease; it was merely starving. The child died the next day. When Pevy went to apply for a pauper's grave to bury her little girl, she was arrested for manslaughter.

The workhouse physician attributed the child’s death to poor nutrition as a result of poverty: ‘Amongst the poor classes the mortality is much greater than amongst the richer class. I account for this by the fact that the poor cannot afford sufficient money to obtain milk, but substitute corn flour and other cheaper and improper food. I do not say that the child had been absolutely starved. I can't say whether the child had been insufficiently fed or deprived entirely of food.’

Pevy was tried at Maidstone assizes for the manslaughter of her child at Margate.107 After the prosecutor had outlined his case against Pevy the Magistrate addressed the Jury: ‘I don’t know, gentlemen, whether you think there is any case made out against the prisoner or not. Are you of opinion that she caused the death of the child by neglect on her part?’ The Foreman of the Jury replied, ‘Your lordship, we do not think that any blame attaches to the prisoner whatever.’ The Magistrate then said ‘I never like to stop these cases before the case has been thoroughly gone into. The offence is a very serious one, and the charge one which ought to be carefully investigated. Are you clearly of opinion that the case is not made out?’ The Forman replied, ‘We are, and find the prisoner not guilty.’

For some of the poor, even gaol seemed attractive. At the Dover Spring Sessions in 1856 Mary Murphy, a servant, was found guilty of stealing forty yards of cotton to a value of 20s from the shop of Edward Rapson.108 Superintendent Marchant reported that when she had been arrested she had been in a state of destitution and he believed she had committed the offence simply to get sent to prison. In this she was successful – she was sentenced to one month imprisonment with hard labour.

References

1. William Batcheller, A new history of Dover, 1828

2. Parliamentary Papers. First report of the commissioners appointed to inquire into the municipal corporations in England and Wales, London, 1835.

3. Kentish Gazette, February 26, 1813.

4. Kentish Gazette, January 1 1813.

5. Dover Express, December 27 1895; copy of a Handbill: A particular account of William Turmain who was executed for burglary on Monday March 8th 1813 at Dover.

6. Kentish Gazette, April 1 1808.

7. Kentish Gazette, June 14 1808.

8. Kentish Gazette, January 5 1813.

9. Kentish Gazette, March 2 1813.

10. Kentish Gazette, March 9 1813.

11. Kentish Gazette, September 19 1817.

12. Morning Chronicle, December 1 1817.

13. Kentish Gazette, December 2 1817.

14. National Archives HO47/56 Part 6, Johnson and Williams.

15. Kentish Gazette, November 28 1817.

16. Kentish Chronicle, May 4 1798.

17. John Fenwick, Observations on the trial of James Coigly, for high-treason, London 1798.

18. Kentish Gazette, April 5 1822.

19. F. Tennyson Jesse, Trial of Sidney Harry Fox, William Hodge and Co., Edinburgh, 1934.

20. S. and B. Webb, English Local Government, Vol. 11, English Prisons under Local Government, Longman Green & Co., London, 1922.

21. Kentish Gazette, June 21 1816.

22. Kentish Gazette, July 12 1816.

23. Kentish Gazette, 27 November 1831.

24. Kentish Gazette, October 29 1813.

25. Kentish Observer, December 12 1833.

26. Dover Chronicle, April 18 1835.

27. The Times, December 26 1812.

28. Kentish Gazette, January 5 1813.

29. John Booker and Russell Craig, John Croaker, Convict Embezzler, Melbourne University Press, Australia, 2000.

30. Kentish Gazette, October 20 1815.

31. National Archives, HO 47/55, Croaker Petition.

32. Kentish Chronicle, May 2 1815.

33. Kentish Gazette, January 31 1815.

34. National Archives, KB 16 25/4, Court of King's Bench, Crown Side, and Supreme Court of Judicature, High Court of Justice, King's Bench.

35. National Archives, KB 21/50, Court of King's Bench: Crown Side.

36. National Archives, KB 36/389, Court of King's Bench: Crown Side: Draft Rule Books .

37. Kentish Gazette, 2 May 1815.

38. Kentish Chronicle, May 26 1815.

39. Kentish Chronicle, October 20 1815.

40. Kentish Gazette, October 24 1815.

41. National Archives, HO 13/28, Home Office: Criminal Entry Books. Correspondence and warrants.

42. Kentish Gazette, August 8 1815.

43. Kentish Chronicle, August 8 1815.

44. Kentish Gazette, December 25 1773.

45. Kentish Gazette, July 21 1807.

46. Kentish Gazette, April 13 1785.

47. Canterbury Journal, February 1 1785.

48. Kentish Gazette, June 21 1816.

49. Kentish Gazette, February 23 1836.

50. Dover Chronicle, January 13 1838.

51. Kentish Gazette, October 9 1810.

52. Kentish Chronicle, June 18 1811.

53. The Case and Trial of Mr Savill, Dover Corporation Laws Made known to the Lovers of Justice, in a Case of the utmost Importance The Trial of Mr Savill, Linen-draper, Margate, Who was falsely and maliciously charged with assaulting Mary Bayly, with intent her carnally to know and to abuse, and found guilty, without proof, after proving his innocence At the Quarter Sessions, Dover, on the 7th of June 1800, Printed by A. Young, London, 1800.

54. Kent Archives, U1453/C571, Letters from W. F. Baylay 1815- 1838.

55. Kentish Gazette, June 9 1826.

56. Kentish Gazette, July 25 1826.

57. Kentish Gazette, November 17 1826.

58. Kentish Gazette, April 8 1834.

59. Kentish Observer, August 1 1833.

60. Parliamentary Papers. Inspectors of Prisons of Great Britain I. Home District, Second Report, London, 1837.

61. National Archives, HO42/24/103 and HO42/24/282: Letters to Henry Dundas 25 Jan. and 28 Feb. 1793.

62. Dover Chronicle, July 21 1838.

63. Dover Telegraph, September 29 1838.

64. Dover Telegraph, April 15 1843.

65. Dover Telegraph, April 5 1834.

66. Edward White, Extracts from the Minutes of the Margate Commissioners, Book 6, 10 January 1816 to 23 January 1833. Manuscript, Margate Library.

67. Kentish Mercury, July 15 1837.

68. Milton and Gravesend Journal, February 17 1838.

69. Kent Archives, Borough of Margate Watch Committee Minutes, 1857.

70. Kentish Gazette, January 17 1832.

71. Kent Herald, March 1 1832.

72. Kentish Gazette, February 10 1832.

73. Dover Telegraph, April 5 1834.

74. Dover Telegraph, July 12 1834.

75. Dover Telegraph, August 2, 1834.

76. Dover Telegraph, July 18 1835.

77. Dover Telegraph, August 13 1836.

78. Kent Archives, Do/JQ/d1, Dover Assizes, Original dispositions 1836.

79. Dover Telegraph, April 6 1844

80. Dover Telegraph, December 28 1844.

81. South Eastern Gazette, April 14 1857.

82. Kent Archives, Do/JQ/d4, Dover assizes, Original depositions 1855.

83. Dover Chronicle, April 18 1857.

84. South Eastern Gazette, December 19 1854.

85. South Eastern Gazette, April 29 1856.

86. Kentish Gazette, April 5 1833.

87. Dover Telegraph, April 5 1834.

88. Kentish Gazette, May 3 1836.

89. Dover Telegraph, April 20 1836.

90. Kentish Gazette, January 9 1838.

91. New South Wales Convict Death Register: 1828-1879.

92. National Archives, HO73/5 Box 2, Return of Justices of the Isle of Thanet to the Constabulary Force Commission, Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire as to the Best Means of Establishing an Efficient Constabulary Force PP 1839 XIX [169], p 1 Returns from local guardians. Cinque Ports – Thanet Division of Dover.

93. Dover Telegraph, July 21 1838.

94. Kentish Mercury, January 19 1839.

95. Dover Telegraph, January 1 1842.

96. Kentish Mercury, January 19 1839.

97. Kentish Mercury, April 13 1839.

98. Kent Herald, January 17 1839.

99. Dover Telegraph, December 31 1853.